Description

Ferdinand Bracke

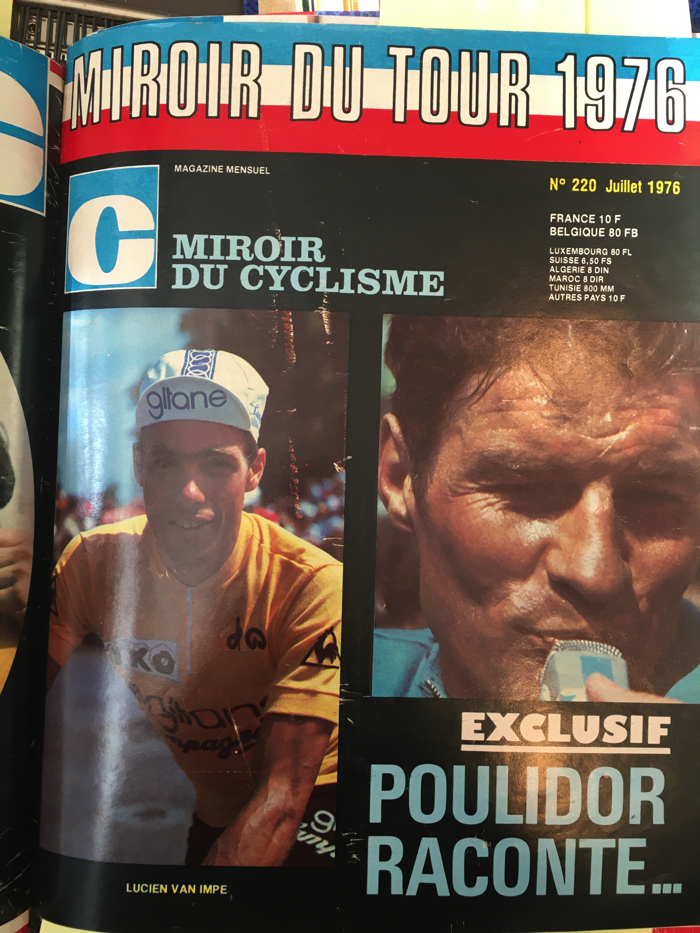

Ferdinand Bracke (born 25 May 1939) is a former Belgian professional road and track cyclist who is most famous for holding the World Hour Record (48.093 km) and winning the overall title at the 1971 Vuelta a España in front of Wilfried David of Belgium and Luis Ocaña of Spain. He also became world pursuit champion on the track in 1964 and 1969.

Biography

Bracke was born in Hamme, East Flanders, Belgium, on 24 May 1939. A rouleur and time trialist, he emerged as an amateur in 1962 by winning the tenth stage of the Peace Race. In May of the same year, he won the Grand Prix des Nations, a time trial race. He turned pro on 26 September 1962, joining the Peugeot-BP-Dunlop team headed by Gaston Plaud.

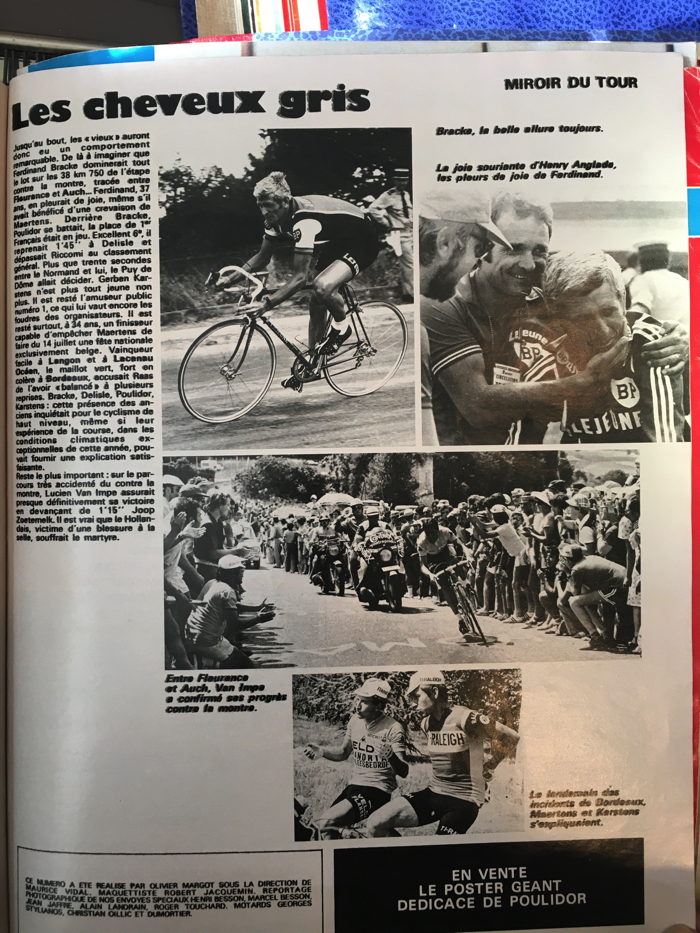

In the following years, he obtained numerous prestigious victories on road: he won the Trofeo Baracchi, together with Eddy Merckx, in 1966 and 1967, a stage in the 1966 Tour de France and the final time trial of the 1976 Tour de France. He finished 3rd overall at the 1968 Tour de France. In 1971 he won the Vuelta a España, beating compatriot Wilfried David (who placed second) and Spaniard Luis Ocaña (who placed third).

He became world champion in track pursuit in 1964 in Paris and again in Antwerp in 1969, then winning second place in 1972 and 1974 and placing third in 1973. On 30 October 1967, he recorded the hour record with 48,093 kilometers at the Olympic Velodrome in Rome, becoming the first cyclist to reach the milestone of 48 kilometers. The record, broken the following year by Ole Ritter, remained the best performance on the track below 600 meters of altitude for a long time.

In 1978 he ended his cycling career and took over a furniture business with his wife. On 17 February 1979, Bracke was bid farewell to cycling at a cycling gala in the Sports Palace in Ghent.

Honors

In 1967 Bracke was voted Belgian Sportsman of the year (the first in history to receive this award) and was awarded the Nationale trofee voor sportverdienste.

*******************

Henry Anglade

Henry Anglade (born 6 July 1933 in Thionville, France) is a former French cyclist. In 1959 he was closest to winning the Tour de France, when he finished second, 4:01 behind Federico Bahamontes. In 1960 he wore the yellow jersey for two days.

Professional racing

Henry Anglade turned professional in 1957. In 1959, he won the Dauphiné Libéré, a mountainous stage race over a week; then the national road championship. He came second in the Tour de Suisse and then in the Tour de France, behind Federico Bahamontes but in front of Jacques Anquetil and Roger Rivière. In that Tour, Anglade – riding for the regional Centre-Midi team – was the victim of the tactics of Anquetil, Rivière, and others in the French national team. They preferred to see Bahamontes take the Tour de France rather than Anglade, who was unpopular among French riders and, had he won the Tour de France, would have earned more than Anquetil and Rivière in the post-Tour criteriums that were then an important part of riders’ incomes. Bahamontes was both Spanish and a poor rider in round-the-houses races and so of little threat. On top of that, Anquetil, Rivière, and many other French stars were represented by Daniel Dousset, one of the two agents who divided French cycling, whereas Anglade was represented by the other, Roger Piel. That was why Anglade had been left out of the national team to ride for a regional one.

At the stage finish in Grenoble, Dousset was there to meet Fausto Coppi, who was Bahamontes’ sponsor, and the riders in the national team whom he represented. Émile Besson wrote in L’Humanité: “Dousset offered contracts for criteriums by the shovel load for after the Tour of Spain. Anglade’s head, second in Paris, had fallen.” Fans worked out what was going on and Anquetil was whistled and jeered as he entered the Parc des Princes on the last day. Anglade said: “I’ve got no regrets about it. Racing is like that. And anyway I make it a principle to live without regrets.”

Anglade was not the strongest of riders but made up for what he lacked with a good tactical sense. He was an eloquent speaker and popular with journalists. Riders, however, disliked him for what they perceived as his bossiness and gave him the nickname Napoleon, which referred as well to his smallness.

Anglade joined the Pelforth-Sauvage-Lejeune in 1963 and finished the next year’s Tour de France in fourth place, behind Anquetil, Raymond Poulidor, and Bahamontes. He also came fourth in the 1965 race, behind Felice Gimondi, Poulidor, and Gianni Motta.

His health disturbed his 1966 season and he spent his last season, 1967, as a team rider for Raymond Poulidor. He rode in ten editions of the Tour de France and finished all but his last. His places in the general classification were always in the top 20 aside from his first Tour where he finished 28th, but thereafter he finished 17th, 2nd, 8th, 18th, 12th, 11th, 4th and 4th.

1959 national championship

The 1959 national championship used the car racing circuit at Montlhéry. Anglade was in a leading group with five laps left. Louison Bobet was leading the chase. The commissaries had got as far as clearing following cars out of the way so that the chasers could regain the leaders. Anglade dropped to the back of his group, had something to eat, and set off alone when Bobet and the others were nearly on them. The others hesitated and the chasers eased up when the two groups came together. Anglade was convinced he’d won and eased up with 100m left to raise his hands in victory.

“He thought he’d won,” said a report, “and sat up to salute the crowd. L’impudent! He had barely crossed the line when he was passed by Jean Forestier and René Privat, who had also broken away and were sprinting for second place.”

1965 national championship

The Pelforth team met the night before the championship at a hotel near the circuit. The manager, Maurice de Muer, said: “Anyone intending to be champion of France, raise a hand.” Four put up their hands, including Georges Groussard and Anglade. Anglade said: “Right, that’s three too many. You three who fancy the jersey, I consider you adversaries. As for the rest of you with no particular ambitions, ride for me because I’m going to be French champion.”

Another Pelforth rider, Hubert Ferrer, broke away alone for 170 km. He was caught 30 km from the line. The peloton was tired from chasing and repeated attacks. Raymond Delisle went away when Ferrer was caught. Anglade caught him, the two stayed together for a while and then Anglade went away alone with five laps to go. He said:

- I knew that behind me, Jacques Anquetil and Raymond Poulidor would be neutralizing each other, so I decided to keep the peloton at a minute. I realized quickly that I had a friend in the announcer. I could hear the loudspeakers perfectly right around the course and when he said ’55 seconds’, I accelerated. When I heard ‘1m 5s’, I eased back a bit to recover. It worked so well that I crossed the line a minute and five seconds ahead of Poulidor and Anquetil.

General de Gaulle

Anglade was in the French national jersey when the race stopped unexpectedly at Colombey-les-deux-Églises to greet Charles de Gaulle, the president, in his village. Anglade said:

- I had stopped to relieve myself. I was just coming back up through the following cars when Jacques Goddet called me to say that the General was on the course. He asked me ‘Could you imagine stopping?’, a strange question to ask me, Napoleon, given that I used to get fined if I put a foot down on the road. I said we could stop but provided there was no penalty. I went up to the front of the race to warn the leaders, Nencini, Adriaenssens. In the wood of La Boisserie [de Gaulle’s estate], the bodyguards were already across the road, and so we all stopped. The general came down the slope, he greeted me first and then Nencini, telling him he was going to win, and then he went back and we set off again. I often wondered why he had spoken to me first and then later I got the answer. The General was vising Lyon and I was one of those invited. The chef du protocole introduced me and the General said ‘One does not introduce Henry Anglade’. I asked him why and he said ‘You were wearing our flag and I owed it to you’ [je vous devais bien ça].

It was the first time the Tour had stopped during a stage.

Downhill race

Henry Anglade’s downhill race with Gastone Nencini has become part of the legend of cycling. Anglade was a proud rider and Nencini one of the fastest down hills. “The only reason to follow Nencini down mountains is if you have a death wish,” was how Raphaël Géminiani put it. It was in trying to follow Nencini down a mountain that Roger Rivière missed a bend, crashed over a wall and broke his spine.

Anglade and Nencini met at a col in the Dolomites during the Giro d’Italia. The weather was bad and a snowstorm had forced 57 riders to abandon that day. Anglade said:

- I couldn’t tolerate the idea that Nencini was the best descender of the peloton. I said to him, call the blackboard man, we’ll do the descent together and whoever comes second pays for the aperitifs this evening. So he called the ardoisier and asked him to follow us. The road was of compressed earth. We attacked the drop flat out. I let Nencini take the lead so that I could see how he negotiated the bends before attacking him. In the end I dropped as though I was alone. At the bottom, I had taken 32 seconds out of him, written on the blackboard. I was really tickled. I had beaten Nencini. The next time I saw him was that evening in the hotel I was staying at. He had just bought me an apéritif!

Doping

Anglade raced at a time when riders made much of their income in the criterium races, for which they were paid start money as well as prizes, that followed the Tour de France. In 1967, in the concern about doping that followed the death of Tom Simpson in the Tour four months earlier, Anglade said: “I’ve driven 4,000km in three days, I’ve ridden 400km of race with only six hours in bed. Do you think I could have done that contenting myself with drinking lemonade?”

Retirement

Anglade crashed in a criterium at Montélimar in 1966 and broke his spine. He said:

- I was mixing it with Raymond Poulidor [on s’amusait à se tirer la bourre avec Poulidor]. I was in front and he was trying to join me. We were approaching a bend and I stepped on the gas and unfortunately, my pedal touched the road. I flew off the bike: fractured vertebral column. I was at the end of my contract with Pelforth and it wasn’t being renewed. Antonin Magne, the manager of Mercier, going through Roger Piel, my agent, opened the door for me. For me it was a real pleasure. But I never really came back to my old level. So I wrote a letter of resignation, explaining that I didn’t deserve to be paid to be a racer. Magne phoned me: he’d never seen such a thing. The book of my career closed.

Anglade left cycling on 13 September to work for the Olympia typewriter company with one of his cousins. He wanted no more to do with cycling until, in 1975, the Lejeune brothers who ran a bike factory in Paris and sponsored a team invited him to join. He managed Lejeune-BP in three Tours de France, where he managed Roy Schuiten, Ferdinand Bracke and Lucien Van Impe. He said the team lacked leaders and wasn’t a success.

Anglade learned how to make stained-glass windows and designed and created those in the cyclists’ chapel, Notre Dame des Cyclistes at Labastide-d’Armagnac in the Landes. He said:

- Ever since I was really tiny, I have always admired stained-glass windows. When I was a choir boy, I couldn’t follow the Mass because I was in ecstasy in front of a window. Somehow I had it in my skin. Five years ago I went to a demonstration of how the windows were made and I flipped. I signed on for more. I made a window of the Virgin, which I gave to Father Massié for the 40th anniversary of the Notre Dame des Cyclistes at La Bastide d’Armagnac. I was really proud and happy.

The professional cyclist’s habit of endorsing commercial products never left him. in 2008 he endorsed the brand of hearing aid that he wore.

Recent Comments