Description

A SHORT HISTORY OF PARIS-BREST-PARIS

©Bill Bryant 1999, 2003, 2021 (rusa.org)

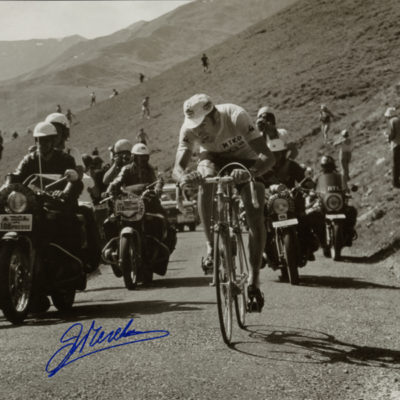

Francois Neuville (Bel), Bertin-Wolber Team

Paris-Brest-Paris, 3 Sept 1948

First run in 1891, the 1200-kilometer Paris-Brest-Paris is a grueling test of human endurance and cycling ability. “PBP,” as it is commonly called, is organized every four years by the Audax Club Parisien, and its Paris-Brest-Paris Randonneur is the oldest bicycling event still run on a regular basis on the open road. (An Australian track race and a British hill climb race both started in 1887 and continue into modern times.) Beginning on the southwestern side of the French capital, PBP travels west to the port city of Brest on the Atlantic Ocean and returns (mostly) along the same route. Today’s randonneur cyclists, while no longer riding the primitive machines used 130 years ago over dirt roads and cobblestones, still have to face up to rough weather, endless hills, and pedaling around the clock. A 90-hour time limit ensures that only the hardiest randonneurs and randonneuses earn the prestigious PBP finisher’s medal and have their name entered into the event’s Great Book, along with every other finisher going back to the very first PBP. To become a PBP ancien (or ancienne for women) is to join an elite group of cyclists who have successfully endured this mighty challenge. No longer a contest for professional racing cyclists (whose entry is now forbidden), PBP evolved into a timed randonnée or brevet for hard-riding amateurs during the middle part of the 20th century.

1921 Paris-Brest-Paris, At The Start Line

The Racing Years

In 1891, people didn’t know what could be done on the bicycle. Some medical experts of the day decried its alleged harm to the human body, and some members of the clergy said the same about potential damage to the rider’s soul. Some women boldly insisted on riding bikes, just like men! Racing on velodromes in front of throngs of spectators had begun ten years earlier, and cycling around town by wealthy enthusiasts who could afford a machine was common enough, but the idea of covering long distances on the open road was still in its infancy. Nonetheless, as the turn of the century approached, ideas about what this fascinating new invention could do began to expand.

Early attempts at road racing and touring overhill and dale had started some years before, but they certainly weren’t at all frequent. Rutted and dusty in dry weather or muddy after rain, the unpaved roads of the time were frequently in poor condition. Encountered mostly in cities, bumpy cobblestones were often destructive to the fragile bicycle wheels as well. In spite of that, in the spring of 1891 the inaugural Bordeaux-to-Paris was held, a race on the open road that covered a whopping 572 kilometers. It took the winner, G.P. Mills of England, 27 hours to arrive in Paris. The sheer audacity of the event captured the public’s attention, and newspaper sales shot up for days before and after. This wasn’t lost on the editor (and devoted cycling enthusiast) of Le Petit Journal, Pierre Griffard. Also not lost was the fact that foreign riders had dominated Bordeaux-Paris from start to finish—the first Frenchman was a distant fifth place.

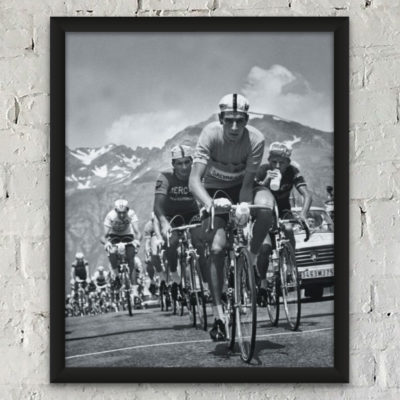

Paris-Brest-Paris

Buffalo Velodrome, 6 September 1931

Emile Decroix (4th), Leon Louyet (2nd) & Ernest Mottard (12th)

The inaugural Paris-Brest-Paris was announced for early September of 1891. Griffard intended it to be the supreme test of bicycle reliability and the willpower of its rider. He didn’t miss the mark: at 1,200 kilometers, PBP would make Bordeaux-Paris seem like child’s play. Only male French cyclists were allowed to enter. Each rider could have up to ten paid pacers strategically placed along the route to help with drafting and providing mechanical assistance. (Though a common racing practice of the time, only a few of the most well-sponsored racers employed pacers at PBP.) Since reliable automobiles were still some years off into the future, the race would be monitored by a system of event judges and observers connected along the route by train and telegraph. Newspaper reporters would, of course, send their dispatches back to Paris so the public could be supplied with special editions reporting the race as it occurred. PBP also caught the attention of bicycle and tire manufacturers, wanting to show the cycling-crazy public that their products were superior to other brands.

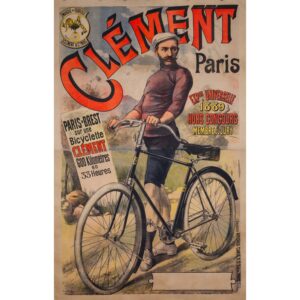

1891 Paris-Brest-Paris. Clement Bicycles featuring Joseph Jiel-Laval

Unlike the modern rural PBP route, which successfully avoids the busier highways west of Paris, the original route followed the Great West Road to Brest, or Route Nationale 12 as it came to be known, through the cities of La Queue-en-Yveline, Mortagne-au-Perche, Pré-en-Pail, Laval, Montauban-de-Bretagne, Saint Brieuc, and Morlaix. Riders were required to stop in each of these contrôle towns and have their route book signed and stamped at each checkpoint, a practice still done today. No one knew how long it would take to cycle the extraordinary distance, and nay-sayers were convinced it couldn’t be done at all; some even claimed that some foolish riders might die in the attempt! During that summer of 1891, in a much simpler place and time than ours, French newspapers were filled with stories and speculation about the upcoming test, and the public’s imagination was riveted on this outstanding wager of audacity and determination. Over 400 riders entered the inaugural PBP, but many apparently came to their senses; 206 brave cyclists eventually set off just before sunrise on September 6th amid great pomp and ceremony. How many, everyone in the vast crowds wondered, would make it back to Paris in one piece?

Widely reported in the press and discussed by the general public, the first edition of PBP was a huge success. The winner, Charles Terront, triumphantly, albeit wearily, pedaled into Paris at dawn three days later after slightly less than 72 sleepless hours on the road. Despite the early hour, over ten thousand cheering spectators were awaiting his arrival. His was an epic ride against his competitors and nature itself, and Terront became a national celebrity. A little over half the starters gave up along the way and got themselves to the nearest train station, while one hundred haggard survivors continued to trickle into Paris over the next seven days. Along with prize money for 17th place, these lion-hearted heroes were all given a handsome commemorative medal inscribed with their name and time, and the legend of Paris-Brest-Paris was born.

Excerpt from Randonnerus USA, rusa.org. Read the full article by clicking here.

Photos from The Horton Collection Archives

Recent Comments